John Coplans, Self-Portrait, Fingers Front, 1999. Gelatin silver print, 24 × 31in. (61 × 78.7 cm) Mount (board): 26 1/16 × 33 1/8in. (66.2 × 84.1 cm). Image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

My Father’s Hobby in Two Stories

by Aidan O’Brien

1

The body lay out where earlier other men had been playing dead. Flesh crinkled and bulged around the wound, rimming the hole where the bullet had entered the man’s cheek—flesh like the screw threads of an open bottle’s mouth, like waiting for a cap. The sinking summer sun made a pink meringue of the clouds that floated overhead in low lines, the gaps between showing a plum sky.

Three men clustered around the body. One offered to carry it. Another stopped him. One offered to run up to the visitor’s center, where they had a pay phone. The others agreed to stay. Waiting, they instinctively faced in opposite directions. Neither looked at the corpse, disturbed by its stillness, by the manner in which its legs were lying, not like limbs but like heavy, twisted cords. Smudges of dirt around the dead man’s mouth reminded one of the men of his son’s face after an encounter with a candy bar. A paramedic would later describe stripping the dead man of his replica Confederate uniform as one of the oddest experiences of her life.

The reenactment always ended with a celebration, as though both sides had won the battle. Confederate and Union men, unaware anything was amiss, linked arms, drank whiskey out of secreted flasks—alcohol was officially forbidden—and congregated around flickering bonfires that dotted Seminary Ridge in a horseshoe around to Barlow’s Knoll.

Somehow, at some point in the evening, somebody found out about the killing. Soon, everybody knew: the fact of the killing, that is, not the victim’s identity. My father, wearing his Union uniform, wandered from group to group, asking the men what they thought of the situation.

Mingling with a group of Confederates on Seminary Ridge, he took an interest in a man named James Barclay when he noticed him standing slightly apart from the others, casting repeated, lingering glances across the surrounding fields. My father approached, introduced himself, and asked James what he was looking for. “My friend,” James said. “I don’t know where he is.”

“I’m sure there’s no need to worry,” said Dad. “Who’s your friend? Maybe I know him.”

“His name is Clark,” said the man.

“Maybe he went home,” said Dad. “I’m sure he wasn’t . . .”

“He wouldn’t leave without telling me.”

“He probably just got turned around. I bet he’s looking for you.”

James’s eyes were soft with swallowed emotion.

Dad put an arm across James’s shoulders. He had not been drinking. Dad did not need alcohol to become quickly, startlingly affectionate. A tall, gangly fellow, he was forced to lean over slightly to accommodate the smaller man. “It’s going to be alright,” Dad said.

A week later, after the identification of the dead man had been released to the public, Dad loaded a few items onto the back of a rented pickup truck and drove from Connecticut to Alabama—a fifteen-hour trip split by a single pit stop in a Virginia rest area twenty minutes outside of Harrisonburg, where he slept for five hours on the reclined passenger-side front seat with the windows open. He woke at 4 a.m., entered the twenty-four-hour McDonald’s, used the bathroom, and purchased two Big Macs. He ate one immediately and kept the other until he became hungry again, which occurred as he was driving somewhere in the middle of North Carolina. He arrived at James’s home on the afternoon of Saturday, July 18th.

James Barclay lived in a typical two-story suburban home with a small, fenced-in yard in the back. From the conversation they’d had on Seminary Ridge, he knew James to be neither married nor a father.

At first, James struggled to identify the man standing on his porch holding a bottle of Speyburn malt whiskey and peering in at him through the mesh door.

“Andrew Wagner. We met at the reenactment.”

My father said that, just like everybody else, he’d been following the story of the man who’d been shot. “I felt a special sort of sick when they released his identity. I remembered you saying your friend’s name and my telling you that everything would be fine.”

Sitting on a couch in James’s living room, Dad accepted a cup of coffee. It sat before him on a coaster on the glass-topped coffee table, untouched, its steam a swaying exhale. He sat with his elbows on his knees, leaning in the direction of James, who perched on the front edge of a squat, blue armchair. James told Dad that he had nothing to apologize for. How could he have known? Dad told James that these reassurances were appreciated but did nothing to mitigate his guilt. “And more importantly,” he went on, “I don’t want this to be about me.”

Gesturing to the bottle of Speyburn, he suggested they open it. James retrieved two tumblers and a little paring knife which my father used to deconstruct the bottle’s black plastic seal. He waited for James to drink first. He continued: “Like I was saying, I didn’t come here to talk about me. Clark was your friend. It’s a terrible loss.” James looked down at his lap, where he held the drink. He sipped it again, and the muscles in his neck braced against the flavor.

My father expressed hope that the funeral had been a good one and that the opportunity to celebrate Clark’s life with so many of Clark’s loved ones had provided some sense of closure. James said that the funeral had been fine. “Just fine?” Dad asked. James nodded. “Isn’t that always the way,” said Dad. “These formal events can never really capture the essence of a person, can they?”

“I agree,” said James.

For the next hour, my father continued asking questions about Clark (a funny man, claimed James, though a little awkward around women) and James’s friendship with him (they’d met in college, in a statistics course). There was a rhythm now to the flow of my father’s low, soothing speech and the sip sip sip of liquor. Every time James threatened to empty his tumbler, my father picked up the bottle, reached across the coffee table, and refilled it for him.

“Which of you got the other one into reenactments?” he asked.

“Clark,” said James. “His dad took him to them when he was little. I thought it sounded dumb, but I did it because Clark wanted me to and . . .” He paused, unable to continue speaking. He pursed and contorted his lips for a moment, sadness as a sour candy. “It’s a great community,” he said. “The reenactment guys. I don’t have to tell you.”

“No, you don’t,” Dad said. “It’s a family.”

James began to weep. His shoulders shuddered, and his mouth opened, and his lips pulled back from his slightly parted teeth, and he breathed in gasps, his gut punching outward and sucking back in. From the faded pattern of the tan lines on his neck and the pale skin partially masked by thick black hair along his bare calves, it was clear that he had not gone outside much in the past weeks. My father reached over and took the tumbler from James’s shaking hand. “I’m sorry,” said James.

“Not at all. You miss him.”

“I miss him,” James repeated.

“Here,” said Dad. “Come outside.”

Dad took James to see the pine box in the back of the rented pickup truck. He’d kept it covered in a blue tarpaulin on the drive down to protect it from the elements, and when he pulled the cover back, James’s eyes got wide, and he reeled and almost collapsed in the driveway.

“Is Clark in there?” he asked, absurdly, drunkenly, almost yelling.

Dad caught his shoulders. “No, no, of course not.” He guided him forward. “It’s just a box. A pinewood casket. I made it. There’s just rocks in it.”

“What’s it for?” asked James.

“It’s for us to bury,” said Dad.

They stood at the end of James’s driveway, one man in a bathrobe, a hand half-outstretched to tentatively touch the pale casket, the other man with his arms still halfway wrapped around the first, supporting his weight, guiding his attention, indifferent to the watching front windows of the houses across the street. From a nearby backyard came the inarticulate exclamation of a playing child, followed by the rounder tone of a parent’s admonition.

“Where did you get this?” James asked.

“I built it.” Dad breathed across his cheek. “I thought that we could give Clark a send-off he deserved.” Keeping one hand on James’s shoulder, my father reached forward and yanked the tarp completely free, revealing two shovels. “I’ve got my uniform with me,” said Dad in a low voice, “and I was thinking that I could put on mine and you put on yours, and we could bury it together. You understand? In memory of Clark. Do for him something he actually would’ve wanted.”

“I don’t—” said James.

“I did this a few years ago,” said Dad. “A few friends and I. All reenactors. It was beautiful. I thought maybe, considering what Clark meant to you . . . what reenactments meant to him . . .”

James looked at my father. Dad’s face—the tanned, stubbled chin; the slight jowls beginning to dangle off the jaw; the light brown eyes and the thick blond-grey hair like machine-shredded paper—it was, to him, the one solid object in a world otherwise warped by heat and drink.

They dressed together, stripping to their boxers in the living room, using each other for balance as they slipped into the pants (grey for James, blue for Dad) that they’d worn at the battle. James’s fingers fumbled with his vest’s brass buttons. “I can’t . . .” he said, too drunk to focus on his hands and finish the thought. “I can’t . . . It won’t let me . . .”

“Here,” said Dad. He fixed up his shirt for him, easing each button through its fabric slot with a soft press. “There we go,” he said. “Good to go.” He put one hand on James’s shoulder and patted his chest with the other. James looked up at him.

Once outside, they quickly overheated in their uniforms. Tugging at their collars, they began to loosen the very buttons just struggled over. They carried the shovels around to the back of the house. “Where?” said my father, and James motioned to a corner of the lawn bordering the fence, where they then began working and were soon sweating and huffing, pausing to sip water or liquor. Neither was in particularly good or particularly bad shape. They shared a slight middle-aged paunch. But soon, both found it necessary to strip off their jackets, vests, and shirts, working bare-chested in pants and boots. A few large rocks needed to be dug around, pried up with the shovels, and lifted by crouching over the hole and hugging the load, causing the grit along the rock’s surface to mingle with the perspiration across their chests, creating brownish trickling trails that navigated down their torsos. It became dark, though never too dark to work, the loss of sunlight supplemented by the glow of suburban life: lamps and light fixtures and wide televisions beaming out from windows, driveway lights and yard lights, and passing car lights. They paused to rest. Dad asked James to tell him a bit more about Clark. James told him about the time his car broke down on the side of the road in Tennessee and he had had to call Clark and ask him to drop what he was doing and drive three hours to come pick him up. En route, Clark had pulled off at a Burger King and ordered a bit of food and his order got lost in the shuffle, and he wound up waiting forty-five minutes for his Whopper before thinking to speak up—and all the while, James was sitting on a dilapidated red bench outside a garage in a town called Pinson and was fretting over whether or not something bad had happened to his friend or he’d given him bad directions or Clark, too, had broken down, “Which would’ve been the sort of thing that would happen to him, if you know what I mean.” Halfway through the story, he began to cry again, doubling over his shovel and sobbing, the fat bunching up on his gut and the skin on his back going thin, showing knobs of white spine.

“Hey there,” said Dad, putting a hand on his shoulder. “Hey there.”

They finished digging around 9:30 p.m. They retrieved the casket from the pickup bed, carried it around, and put it in the hole. My father went to the truck and retrieved two replica muskets from the back seat. They put back on their shirts, vests, and jackets, peeling the coarse fabric over their sweaty skin. They each took a gun. “We can only do this once,” said Dad. They fired powder into the open air. Dad started singing. He sang “Goodbye, Old Glory,” and James listened and even began crying again when my father came to the chorus.

“Alright,” said Dad, “it’s time for me to go home.”

“Not far, I hope,” said James.

“Just a couple of hours,” Dad said.

He left James standing in his backyard.

He made it back by the following evening. As he pulled into the driveway, he saw me playing in the backyard. He yelled, “There you are! I’ve been half across the country looking for you.”

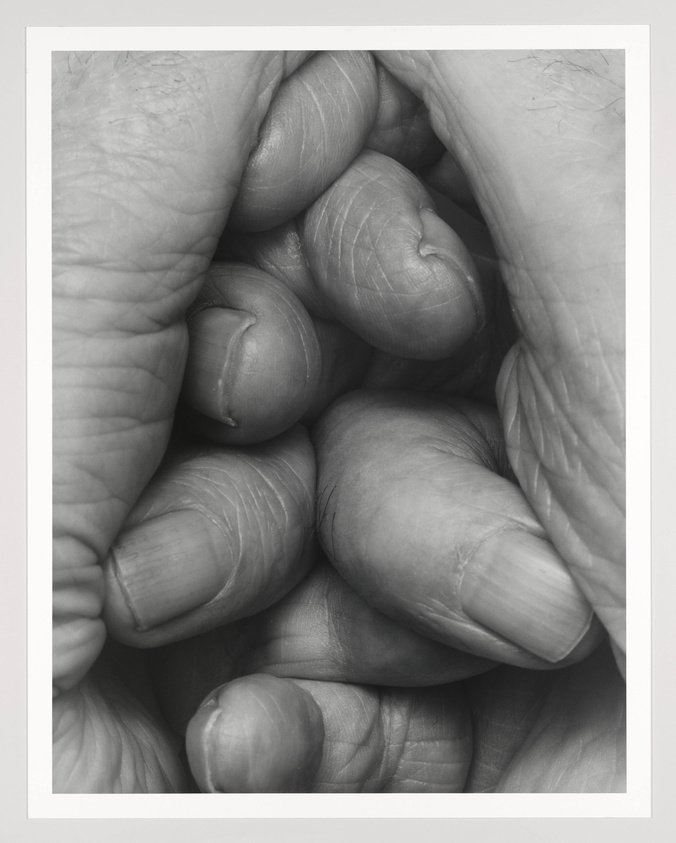

John Coplans, Self-Portrait (Interlocking Fingers, No. 18) 2000. Gelatin silver print mounted on board, 31 1/8 × 24in. (79.1 × 61 cm) Mount (board): 33 1/8 × 26 1/16in. (84.1 × 66.2 cm). Image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

2

One evening, when I was fifteen, my father asked me if we could reenact our going-to-bed routine from when I was very little. “Say, three years old.” I told him that this request made me uncomfortable, and an argument ensued in which I tried to explain, absurdly, obviously, that I was no longer an infant. He responded by saying, over and over again, that it would only be as if I were three, and that this exercise mattered to him. Tears formed in the corners of his eyes. “Please, Alex.” He insisted that there was nothing wrong with his request, that it was a perfectly natural thing for him to want. Finally, I agreed, but with one caveat: He could not bathe me. This upset him, but I stood my ground. We ate baked cod for dinner. I did my homework. We went into the bathroom together so that he could brush my teeth for me. From the toiletries basket in the closet, he retrieved a tube of strawberry-flavored children’s Tom’sbrand toothpaste and a baby-blue children’s toothbrush that he must’ve bought specifically for the purpose. He applied a dollop the size of a grain of rice to the white bristles. He instructed me to open my mouth. I closed my eyes and let him brush my teeth. He started in the bottom left corner and worked his way around. After brushing my bottom teeth, he handed me a glass of water and instructed me to “swish and spit.” He asked me what sort of animal spat out water like that. Was I a whale? Was I shooting the water out of my blowhole? He told me to open my mouth again. I did. He made low, groaning whale noises as he turned his attention to the upper part of my mouth. He told me that when I was little, I would sometimes bite down on the toothbrush, mussing the bristles and growling like a tiger. I could see that he wanted me to do it. I bit down. The toothbrush’s rubbery neck warped between my teeth. A low rumble scraped in my throat. He told me to spit and asked if I needed to go potty. I shook my head. He guided me upstairs with a hand on my back. In my bedroom, he dressed me in my pajamas. When I crawled under the covers, he climbed on top of them beside me. He read from The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, the chapter in which Christopher Robin organizes an expedition (an “expotition,” Pooh calls it) to find the North Pole. He asked me to sound out short words. “What’s that?” he’d say, pointing, and I’d say it: “wood,” or “fog,” or “rabbit.” He did not want me to pronounce them so easily. I began sounding them out as though I were really having trouble. “Wo-ooo-d.” “Re-ra-bit.” “Wat-water.” As I struggled, he would whisper to me that I was doing well, that I should keep going, that I was getting it. Afterward, he reached across me to turn off the lamp atop the little bookcase beside my bed—not filled with children’s books, as it once was, but by my high school reading: Great Expectations, The Crucible, The Color Purple. In the dark, he lay beside me, one heavy arm over me, fishy breath spilling across my cheek. He sang as he used to sing for me at bedtime. First, “Stay Awake”from Mary Poppins, in a low, growling voice that scraped in and out of audibility, then “All Through the Night.”He lay there for over an hour until I fell asleep. As he clambered around me and out of the bed, I half-woke. I saw him as a dark shape, moving with care, shifting limbs slowly. “Shhhhhh, shhhhh,” he said, placing a palm on the side of my face. I feigned settling, sleeping. He left. The door clicked shut behind him. I saw the hall light reaching in from beneath the door. I’d gotten used to the feeling of his arm across my chest, its heaviness. I piled blanks and pillows atop myself to recreate the sensation.

Published March 10th, 2024

Aidan O'Brien's stories have appeared in The Greensboro Review, Levee Magazine, Bodega, Barren Magazine, Failbetter, and elsewhere. He earned his bachelor's at Sarah Lawrence College where he received the creative writing department's Jane Cooper Scholarship. He is currently a student at The MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson.

John Rivers Coplans (24 June 1920 – 21 August 2003) was a British artist, art writer, curator, and museum director. A veteran of World War II and a photographer, he emigrated to the United States in 1960 and had many exhibitions in Europe and North America. He was on the founding editorial staff of Artforum from 1962 to 1971, and was Editor-in-Chief from 1972 to 1977.